Olive Oil Pottery

This generic name comprises ceramic objects used for transportation, storage, and consumption of olive oil products. For instance, thousands of containers with over 120.000 kg of oil were found in the excavations of the Ebla palace in northern Syria, the pieces are believed to be over 3500 years old. The Sumerian tablets of the palace archives, written in cuneiform writing, mention the tax applied to different quality olive oils. The most delicate oils were used for perfume manufacturing where essences such as myrtle or incense were added. Descriptions of whether oils were new, bitter, aromatic, or scented were also found. The oil from northern Syria was already imported and considered a precious item in Central Mesopotamia. Back in the Mycenaean time, Cretans already kept oil in large jars for human consumption.

Oil was used in many different occasions: for rituals (mostly religious and funerals), for lighting, personal cleanliness, yet also as a luxury item to be exchanged or gifted. For instance, it is thought between 200 and 330 kilograms of oil were used per household in Athens.

Oil for Lighting and Oil Containers

Evidence has been found that crushed olive pits were used as fuel in Crete. Oil lamps were the most popular utensil for lighting. In them, a vegetable fiber wick was placed going from the small oil-storing plate to the beak-shaped nozzle, where the flame was located. A similar model was found in the Syria-Palestine region and was adopted later on by the peoples of many Phoenician cities, including ones in the western Phoenician centers of the Iberian Peninsula.

The evolution of oil lamps –Phoenician, Greek and Roman– can be observed in the pieces above.

More elaborated, expensive, and precious oil lamps were made from copper in different shapes and sizes. Simpler ones were made on the lathe and coated with shiny black glaze. These clay lamps were popular during the Roman period, in the 2nd century BC, and were made using a mold and slip colors ranging from yellow to red. Some other lamps were very elaborated and decorated with mythological, erotic, or folk scenes, etc. Christian themes we also introduced during the fourth century.

In Athens, lighting was often considered a luxury, associated with social domestic gatherings, banquets, etc. A small oil lamp could burn up to 50 ml of oil every 7 hours, and given that roughly 10 lamps were needed to properly light a decent sized room, about half a liter of oil was needed to provide light during this time. In Rome, wealthy homes typically had bronze lamps, while the more modest households had oil lamps made of clay. Lamps had between one and five nozzles and hung from high “chandeliers” that had up to eight arms.

Scented Oils, Personal Care and Hygiene, and Funeral and Sacred Rituals.

Elaboration of scented oils dates back to at least of 3500 years ago in Mesopotamia, and later in Crete and Mycenae. The archives of that period mention its different uses: offerings to the gods, ritual anointings of divine statues (many of which were made of wood or ivory and therefore needed its application), wedding ceremonies, anointings of kings and other royals, senior officials, presents to royals or diplomatic representatives, etc.

Oil was also used for personal care and hygiene in Greek society. The usage of olive oil for ointments and massages after exercising in the gym or the arena is well documented. It seems that men used it more than women, given that sports were part of their education. Women used it mixed with water in their baths.

The range of Greek containers for these oils –which were almost perfumes–, was very specific: the aryballos was small oil jar with spherical body, flat-rimmed mouth which allowed the direct application of small doses and the recovery of the excess liquid, acting as an “anti-drip” system. Aryballos often had a single handle extending from the lip to the shoulder of the jar and were used primarily for fragrant ointments.

This same applicator system was used in alabastrons, made of alabaster and similar to the Egyptian flasks of the same name. Alabastrons were small, elongated flasks with a narrow neck, flat-rimmed mouth, and a rounded base, required a stand or support, and were mostly used for fragrant ointments. Both alabastrons and aryballos were about 5 to 10 cm high and decorated with oriental designs.

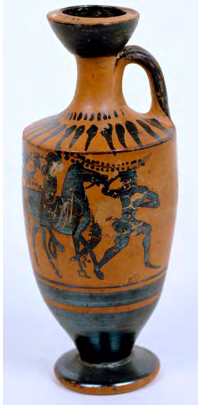

The larger lekythos had an ellipsoidal shape, a curved vertical handle going from the lip to the shoulder and a wider and more prominent neck than the previous vessels. The mouth was different, shaped like a deep cup with a somewhat curved rim, which prevented spills. It was used mainly for ointments.

Alabastrons and aryballos became part of the classical Greek pottery repertoire between the 6th and 4th centuries BC, with black figures, red figures, and black glaze. Lekythoses were already typical of the Attic range in the same period. The iconography behind these vases refers to their use: scenes of young men at the gymnasium or arena, warriors, women taking a bath or giving each other perfumes, etc.

Throughout the 6th century BC, lekythoses started to be used for funerary purposes. Indeed, already in the great Athenian necropolises, the ceramic offerings that included vessels related to the ritual of the Symposium were replaced by one or several lekythoses. This was also seen in the Greek necropolises of Ampurias and other points of the Emporitan area, from where more than a hundred of these vessels have been recovered. The themes that are represented on the vessels are diverse: mythological scenes –where notable importance is given to the Dionysian world, for obvious reasons–, daily life scenes and, especially, combat scenes (also known as “farewell of the warrior”, perhaps allusions to a lost warrior). Towards the mid 5th century BC, a decorative innovation appeared on these pieces: the body of the vessel was covered with a white kaolin paste, which then served as a canvas for decorative painting. This technique was only used for funerary vases, and the represented scenes were very explicit: visits to the tomb with a stele, the deceased, weeping relatives, Hermes, etc. This fashion continued until the beginning of the 4th century BC.

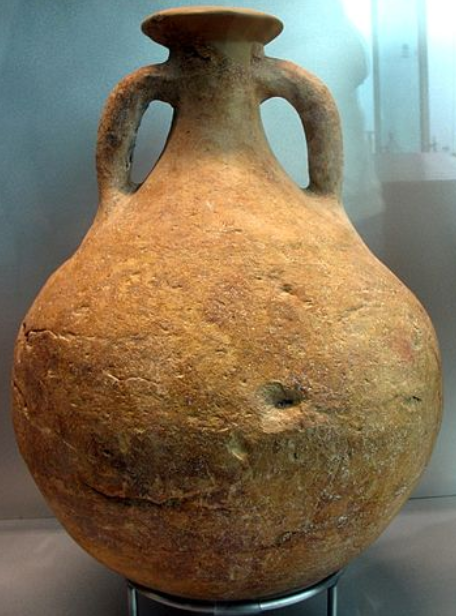

Phoenicians also made containers for perfumed oils, originally in cities of the Lebanese coast. These have been found in 8th and 7thcentury BC necropolises of the Central (Sardinia, Carthage) and Western Mediterranean (Málaga, Cádiz, Huelva, Lixus, Mogador). Also called “mushroom-lipped jugs”, they were round, had a prominent neck and a mouth similar to that of the aryballos, often decorated with a beautiful burnished red slip.

Phoenicians also made containers for perfumed oils, originally in cities of the Lebanese coast. These have been found in 8th and 7thcentury BC necropolises of the Central (Sardinia, Carthage) and Western Mediterranean (Málaga, Cádiz, Huelva, Lixus, Mogador). Also called “mushroom-lipped jugs”, they were round, had a prominent neck and a mouth similar to that of the aryballos, often decorated with a beautiful burnished red slip.

Perfumes in Hellenistic and Roman Times

Perfumeries have been discovered in ancient Greek cities, such as Olynthus, dating back to as early as the 4th century BC. These establishments had a small pressing and storage area (which did not allow the production of large quantities of oil), a small oven and other spaces where olive oil-based perfumes were produced. Several of such small-scale perfume factories were identified in the island of Delos (2nd century BC), famous for famous its many sanctuaries, among which was the one of Apollo. Delos also had an important free-trade port where products arrived from all around the Mediterranean and ended up replacing Corinth (which was destroyed in 146 BC) as the main perfume production and trade hub.

Of the Greek cities of Magna Graecia (latin for “Greater Greece”), Paestum also had a perfume workshop by the city’s forum. The expensive oils of Venafrum were used as a base for perfumes in Campania, where there was a flourishing industry. Some of the best perfumers were in Cumae, but also in other cities such as Puteoli or Pompeii, where workshops have been documented.

In Hellenistic times, the ceramic vessels used to contain oily perfumes were called unguentarium, which were common throughout the Central and Western Mediterranean between the 4th and 1st centuries BC. The unguentarium were small, had a fusiform body, with a moderately high base and a prominent neck. They were carefully varnished black on the inside, making them more impermeable, and had a volume of less than 50 ml (fig. 9). From the 1st century BC onwards, they were replaced throughout the Empire by blown glass flasks –more attractive and inexpensive, yet also more fragile.

Oil as a Prize: Panathenaic Amphorae

The Panathenaic Games, held in Athens in honor of goddess Athena, happened every four years from the mid 6th century BC. Prizes in these games were substantially higher than those awarded at the Olympic, Pythian, Nemean or Isthmian Games, where prizes consisted of a symbolic woolen ribbon or an oak, pine, laurel, olive, or celery wreath. Gold, silver and some oil from Athena’s sacred olive grove, bottled in decorated amphorae, were awarded in the gymnastic and equestrian events. The number of amphorae varied according to the competition, with up to 140 amphorae (35.61 kg of oil each) being awarded to the chariot race winner or 4 amphorae for the winner of horseback shooting on a target. In total, between 700 and 1500 amphorae (15,000 – 30,000 kg of oil) were usually needed for a single competition. At an average price of 55 drachmas per amphora, the winner of the chariot race would make up to 7,700 drachmas (which was equivalent to a modern-day prize of between 250,000 and 300,000€). In most cases, the victors did not keep the oil-filled amphorae but sold or donated them. The containers were sold or exchanged separately, and many of them ended up in Etruria, where they were found as part of grave goods in important tombs.

For each Games, amphorae production contracts were awarded to artisans via public tender, and in the 5th century, the symbol decorating Athena’s shield was the seal of the workshop that made it. Thus, the amphorae painted by Kleophrades bore a Pegasus on the shield; the ones painted by Eucharides, a serpent; those of the painter of Berlin, a Gorgoneion; and so on. All of them were made using the “black-figure” technique, which was in style at the time. This tradition was maintained until the 4th century, though the technique had mostly disappeared, and artists were in the last stages of the “red-figure” technique period.

The subjects depicted on the amphorae were always the same: one side of the vase pictured the Pheidiac statue of Athena Pròmachos, where the goddess appeared armed as usual and flanked by two columns with cockerels, owls, or Nikes (the goddess of victory) –motifs associated with her. They also always carried the ‘ton Athenethen athlon’ inscription, or ‘of the Athens contests’. From the 4thcentury onwards, the name of one of the three city rulers or magistrates, and the eponym of the year, were added. The other side of the vase depicted the game or competition for which it was intended as a prize.

The subjects depicted on the amphorae were always the same: one side of the vase pictured the Pheidiac statue of Athena Pròmachos, where the goddess appeared armed as usual and flanked by two columns with cockerels, owls, or Nikes (the goddess of victory) –motifs associated with her. They also always carried the ‘ton Athenethen athlon’ inscription, or ‘of the Athens contests’. From the 4thcentury onwards, the name of one of the three city rulers or magistrates, and the eponym of the year, were added. The other side of the vase depicted the game or competition for which it was intended as a prize.

Oil for Food

Foxhall, who studied the food-related oil use in Classical Greece, calculated consumption per person and household with surprising results: between 25 and 30 kg per person/year –not far from nowadays’ 50 kg per person/year. Already in Roman times, Athenaeus distinguished different qualities of Greek oil. White oil, made from green olives, was apparently the most digestible, the best of which came from the island of Samos. Oil of other qualities was used to preserve foods such as fish with vinegar or pepper, pork brains, poultry (turtledove, quail, etc.) and other specialties. Oils consumed by the humbler classes were made from ordinary olive varieties that were picked ripe or straight from the ground.

At least from the 4th century on, olives were also consumed and highly appreciated whole –such as those from Tarentum (Magna Graecia)– or in the form of tapenade or olive pâté: Sicily’s epytirum. The olives from the Salento, in southern Apulia, enjoyed great fame from the Republic in Roman times and until the end of the Empire.

Olive oil also made important culinary contributions to Mediterranean cultures –from Asia Minor to Cartagena (a Phoenician city in the southeast Spain) and from Carthage to Marseille– particularly from the Hellenistic period onwards. Greek cities such as Olynthus, Athens or Corinth used ceramic cooking pieces that could be used for cooking with oil, practically identical to those found in Punic Carthage and its area of Hispanic influence (Gades, Ebussus, Carthago Nova), as well as in the Massaliote region (Olbia de Provence).

There are works carried out by different authors that proposed models of use for these vessels:

Lopas: A round, low, and convex-bottomed vessel with a wide mouth and a lid. It first appeared in Greece in the 5th century and was traditionally used for preparing fish in sauce, for which oil played an important role. Lopas were incorporated to the Punic kitchenware in the 3rd century BC and were later also adopted by Romans.

Caccabé or caccabus: A low and wide pot with a convex bottom, with a larger than usual mouth diameter and a lid. This ceramic item could be placed both over hot coals and over fire and was used for cooking fish and meat stews with spices and oil. Though originally Greek, it appeared in the Western Mediterranean in Punic culinary kitchenware around the 3rd century BC and was also adopted by Roman cuisine in the Augustan period.

Patina: This was a low pan with straight or slightly convex sides, flat bottom, large diameter, and a lid. Given its shape, it could be used on charcoal, on the grill or in an oven. Typical from the Italian peninsula, these items first appeared towards the 3rd century BC among the Etruscans. Similar dishes were later found in Campania, with different rim shapes and a thick red slip on the inside, ideal for use in the oven as it provided a non-stick surface. It seems that the patina was first used for cooking fish and also for simmering all kinds of ingredients, which were then cooked in their own sauce. The pieces with a red slip inside were used for preparing patina (a Roman pudding) –the dish from which the vessel takes its name–, cakes or even for baking bread.

Sartago or tagenon: Equivalent to modern-day frying pans, with a flat bottom, open and low sides, and an elongated handle. It was used over coals or fire. Experts unanimously agree that it was used almost exclusively to fry food –especially fish– using oil.

Amphorae for Olive Oil transportation

It seems that it was in the region of Attica where the first ceramic container for transporting oil was produced: a pyriform amphora with a short cylindrical neck, vertical handles and a small flat base. It was painted entirely black except for a metope on the neck which, following some earlier geometric models, always showed a motif of concentric circles between a series of vertical s‘s, which gave rise to its popular name: “SOS” Amphora. Their production may have begun towards the end of the 8th century BC and they have been found throughout the Mediterranean dating back to the 7th and early 6th centuries BC. In the Iberian Peninsula they seemed to be associated with Phoenician trade, as it is documented in Western Phoenician settlements in Andalusia, as well as in Huelva. However, the specificity of its function as an oil container is contradicted by some iconographic representations, such as that of a scene from the famous François Vase of Ergotimos and Kleitias, where it appears behind Dionysus at the wedding of Thetis and Peleus, clearly alluding to its association with wine.

It wasn’t until the Roman Republican period that clearly identified amphorae for olive oil long-distance transport and trade were found.

The first ones can be traced back to Apulia, an important olive-growing region where the present-day cities of Brindisi or Lecce are. Copious amounts of oil were exported from the end of the 2nd century BC and during the first half of the 1st century BC in the so-called brindisian ovoid amphorae, which have been found in Hispania, among other sites. It seems that oil production in the region declined sharply during the second half of the 1st century BC, and amphorae production ceased from the time of Caesar Augustus onwards. However, oil production did not entirely stop, and the golden liquid probably made its way to Rome in other containers that we do not know about. In the northern Adriatic, specifically in the Istrian peninsula, oil was bottled and marketed in the “Dressel 6B” amphorae during the 1st and late 2nd centuries AD. This amphora’s distribution was limited to the Adriatic coasts, the Po Valley and Rome, with little evidence of it being used in the Central and Western Mediterranean.

From the first half, but especially from the end of the 2nd century BC, olive oil from Tripolitania (now northwestern Libya) was exported throughout the Central and Western Mediterranean, as part of an already Roman trade structure. The amphorae used –first cylindrical, then ovoid and then cylindrical again by the 1st century AD– are now known as Ancient Tripolitanian amphorae. Indeed, with a formal Punic origin, they are the first of a whole series of oil amphorae from Tripolitania, which would reach their peak in the 3rd and 4thcenturies AD, when the production of Iberian oil declined. Nonetheless these amphorae were already used earlier, as confirmed by the finds from Pompeii, where many of the oil amphorae were Tripolitan.

From the first half, but especially from the end of the 2nd century BC, olive oil from Tripolitania (now northwestern Libya) was exported throughout the Central and Western Mediterranean, as part of an already Roman trade structure. The amphorae used –first cylindrical, then ovoid and then cylindrical again by the 1st century AD– are now known as Ancient Tripolitanian amphorae. Indeed, with a formal Punic origin, they are the first of a whole series of oil amphorae from Tripolitania, which would reach their peak in the 3rd and 4thcenturies AD, when the production of Iberian oil declined. Nonetheless these amphorae were already used earlier, as confirmed by the finds from Pompeii, where many of the oil amphorae were Tripolitan.

Ibiza was an important olive oil producer too, as shown by studies conducted by several teams. The specific Ibizan amphorae – first known as Mañá, and other variants of this name – were produced from the end of the 3rd century to the 1st century BC. The presence of resin remains on the inside of some of them might suggest multiple usage of the container, which was not unusual in the Punic environment.

The Dressel 20 Amphora and Oil from Baetica

The valleys of the Guadalquivir and Genil rivers were already covered with olive groves at the time of Caesar Augustus. Studies regarding the Roman territorial occupation by M. Ponsich (1974, 1979, 1987 and 1991), together with more recent studies by J. M. Blázquez and J. Remesal, have revealed a whole agrarian and economic structure of production centers, river embarkation points and amphorae manufacturing sites (more than 80 workshops). Their oil was bottled in a characteristic almost spherical amphorae, the Dressel 20, of which millions were exported to Rome and to the Roman enclaves in the Germanic limes and Britannia as part of the Annona Militaris. They constitute a precious element for dating and understanding trade due to their abundant painted inscriptions (tituli picti) and printed seals. Empty weight, oil weight, consular dating, names of the navicularii (shipowners) who transported the amphorae, seals from the manufacturing office, etc., are some of the data that can be found on them.

The Baetian oil reached the port of Ostia and then made its way up the Tiber River by barge, all the way to Rome. Upon arrival, amphorae were unloaded and emptied into skins that were stored in carts inside warehouses. The empty amphorae were all dumped in the same place and eventually –after three centuries– became a small hill.  Monte Testaccio was 1500 m wide and 50 m high and made up exclusively of amphorae debris. Spanish studies and excavations, carried out first by E. Rodríguez Almeida (1980 and 1981) and then by J. M. Blázquez and J. Remesal (1999, 2001, 2003, 2007 and 2010), have turned Monte Testaccio into a huge source of epigraphic information.

Monte Testaccio was 1500 m wide and 50 m high and made up exclusively of amphorae debris. Spanish studies and excavations, carried out first by E. Rodríguez Almeida (1980 and 1981) and then by J. M. Blázquez and J. Remesal (1999, 2001, 2003, 2007 and 2010), have turned Monte Testaccio into a huge source of epigraphic information.